Introduction

Text analysis provides insight into writing style and common themes among a large body of work. For the Southern Life Histories Project, a product of the Federal Writers’ Project under the Works Progress Administration that gathered hundreds of oral interviews to represent Southern American, rural life, analyzing the body of text recorded could show patterns of areas of life that these people were interested in talking about, as well as an interviewee’s way of speaking. By collecting the raw text of several stories from the SLHP and conducting text analysis to compare word frequency, using specified metadata categories as areas of interest, word usage could be interpreted along demographic lines. Differences in word usage among interviewees of different races reveals dialectic choices that were more apparent among black interviewees, but does not appear to be the result of white writers emphasizing dialect among black interviewees.

Methods and Data

In order to conduct text analysis, the program Google Colab was used to create text visualizations. Google Colab is a collaborative medium to run Python code. We ran code that incorporated Pandas, a software library that aids in data analysis. Pandas created data frames out of our Life History spreadsheet data, data that contained multiple metadata categories on selected Life Histories as well as the raw text from each Life History, that could then be used to analyze the word frequency of a particular data frame. Data frames could be a specific metadata category out of our spreadsheet. I was interested in looking at the text variation between interviewees of different races, and created new data frames for interviewees of a “white” or “black” racial identity and writers of a “white” or “black” racial identity, then ran code that generated word frequency graphs for these data frames.

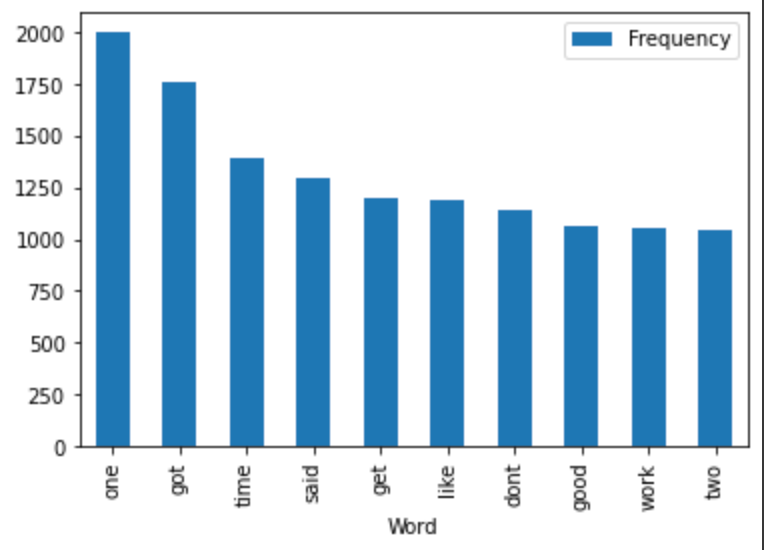

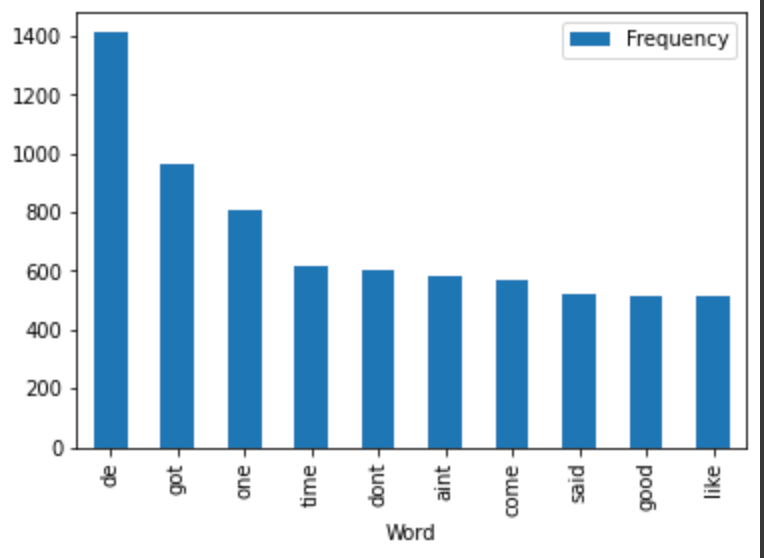

The two graphs above are both word frequency bar graphs of the text from our selected Life Histories. The x-axis are the ten most commonly used words based on some measure—in this instance, word frequency from stories with interviewees labeled as “white” or “black” according to the metadata category “interviewee racial identity.” The y-axis is the amount of times those most common words appear in the text.

Figure 1 looks at the most common words from white interviewees. “One,” “got,” “time,” “said,” “get,” “like,” “dont,” “good,” “work,” and “two” were the ten most used, with “one” being the most used with around 2000 instances. Figure 2 looks at the most common words from black interviewees. “De,” “got,” “one,” “time,” “dont,” “aint,” “come,” “said,” “good,” and “like” were the most used, with “de” being the most used with around 1400 instances.

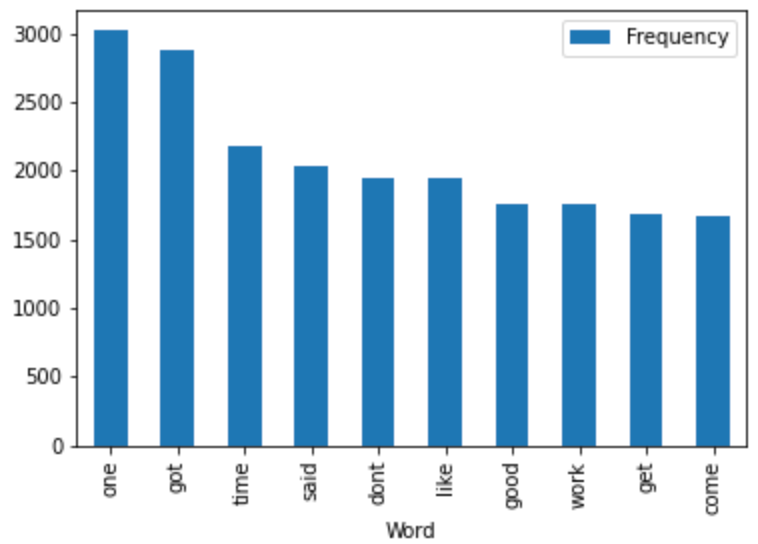

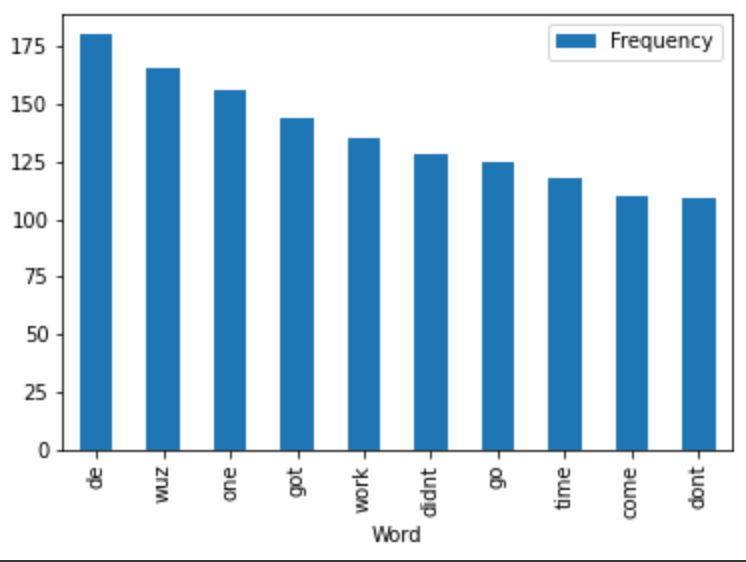

Figure 3 and 4 are word frequency bar graphs of the most commonly used words for the white and black writers of the Life Histories. For word frequency of white writers and white interviewees, nine out of ten words were the same, with the first four words appearing in the same order of frequency. For word frequency of black writers and black interviewees, five out of ten words were the same, and only “de” in both graphs appeared in the same order of frequency, as the most commonly used word for both categories. Word frequency is on a much lower scale for black writers, however, as a much smaller number of writers were black.

Analysis

While there were many overlaps in commonly used words between white and black interviewees, such as “one,” “got,” and “time,” the biggest difference was “de” as the most commonly used word among black interviewees. This word is not among the top ten words for white interviewees. “De” can be assumed to be a dialectic variation of the word “the,” one word that was removed from the text as a stop word before we retrieved our data. As the Life Histories were conducted among a population of United States Southerners, using “de” to emphasize Southern pronunciation with the interviewees is not unusual and provides a more interesting perspective of the text usage in the interviews than the standard “the” would give. However, the inclusion of “de” as the most common word among black interviewees and “aint” included in the top ten, while both words are not top contenders for white interviewees, points to differences in emphasizing dialect based on the race of the interviewee. It is important to remember that the interviews were recorded by writers, and the text is the interpretation of the writers on what was spoken by the interviewees.

One mission of the Federal Writers’ Project was to gather Life Histories of those who were ex-slaves, acquiring oral accounts of life in slavery before those generations were lost forever. The “ex-slave narratives” in the Life Histories have become a point of contention due to the way writers focused on the slave aspect of an interviewees life and could have possibly shaped their narrative to appear to the expectations of what slave life would be like. In her article, “Ex-Slave Narratives: The WPA Federal Writers’ Project Reappraised,” Lynda Hill points out that John Lomax, National Advisor of the Writers’ Project, in response to the first ex-slave narrative, “remarked to Edwin Bjorkman… that ‘the writer of this story has preserved sufficient dialect and particular words so as to make the reader feel the Negro is talking’” (64). Dialect became a tool for writers to make a slave narrative seem more authentic or engaging, and it is clear this dialect style of writing was not as often used for white interviewees. The use of dialect on black interviewees is possibly used for a sense of realism to the audience, that if they know the interviewee is black, they might expect a certain dialect to hook them into the story. Writers might have used this to their advantage to gain Life Histories that were more likely to be published.

In her book, Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project, Catherine Stewart talks extensively of the ex-slave narratives and how Lomaxes dictated how these narratives would be written and published. In a section on “Negro Dialect,” she writes, “Cronyn and Lomax clearly conveyed the expectation of the federal office that all ex-slave narratives be written using a model of dialect in accordance with federal guidelines” (81). Not only was dialect a creative choice for writers of several black interviewees, but it eventually became a requirement, and a requirement with its own rules, standardizations, and guidelines for writers to follow.

Looking at the word frequency of writers based on race could determine a possible explanation for dialectic variations in the Life Histories. Figure 3 shows white writers were not recording the words “de” or “aint” as often as other words in their interviews. Figure 4 shows black writers were using the word “de,” but the frequency only occurs 175 times, only accounting for a fraction of the 1400 occurrences of the word among black interviewees. While it might be easy to assume that white writers emphasized dialect among black interviewees more so than white interviewees, it seems as though writers who were black were more likely to focus on dialect, with “de” and “wuz” being the top two commonly used words. However, more research would need to be done to compare texts that had no data for either interview racial identity or writer racial identity, as well as the most commonly used words of black writers with black interviewees versus white interviewees. The lack of black writers in the Federal Writers’ Project also raises interest in which interviews were words like “de,” “wuz,” and “aint” recorded, and if certain writers repeated this style and added to the word usage.

Conclusion

Considering the studied impact of the dialect of the ex-slave narratives and the higher frequency of dialect apparent in black interviewees, dialect was emphasized more often among black interviewees, probably for the purpose of an authentic story. However, who exactly was writing in dialect for black interviewees remains unclear. White writers did not appear to have high usage of dialect, and black writers only made up a small portion of dialect used. It would be crucial to look at word frequency for stories considered “ex-slave narratives” and how many of these stories make up the SLHP as a whole, as well as look into which writers used dialect and how often they used it. Further, it would be interesting to know if dialect was apparent among white interviewees as well, but was not recorded as there was no interest outside of an “ex-slave narrative.” The choice to use dialect in the Life Histories appears to be a complicated story with racial markers among both writers and interviewees.

Works Cited

Hill, Lynda M. “Ex-Slave Narratives: The Wpa Federal Writers’ Project Reappraised.” Oral History, vol. 26, no. 1, 1998, pp. 64–72, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40179473.

Stewart, Catherine A. Long Past Slavery: Race and the Federal Writers’ Ex-Slave Project during the New Deal. The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

Leave a comment