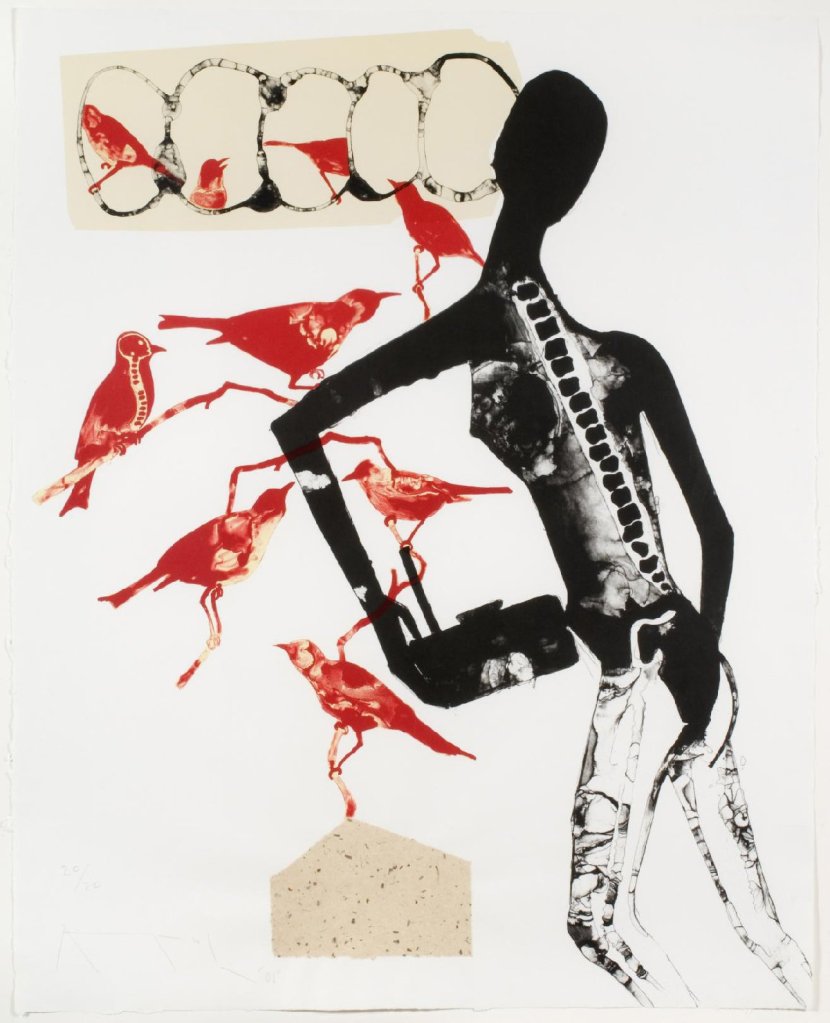

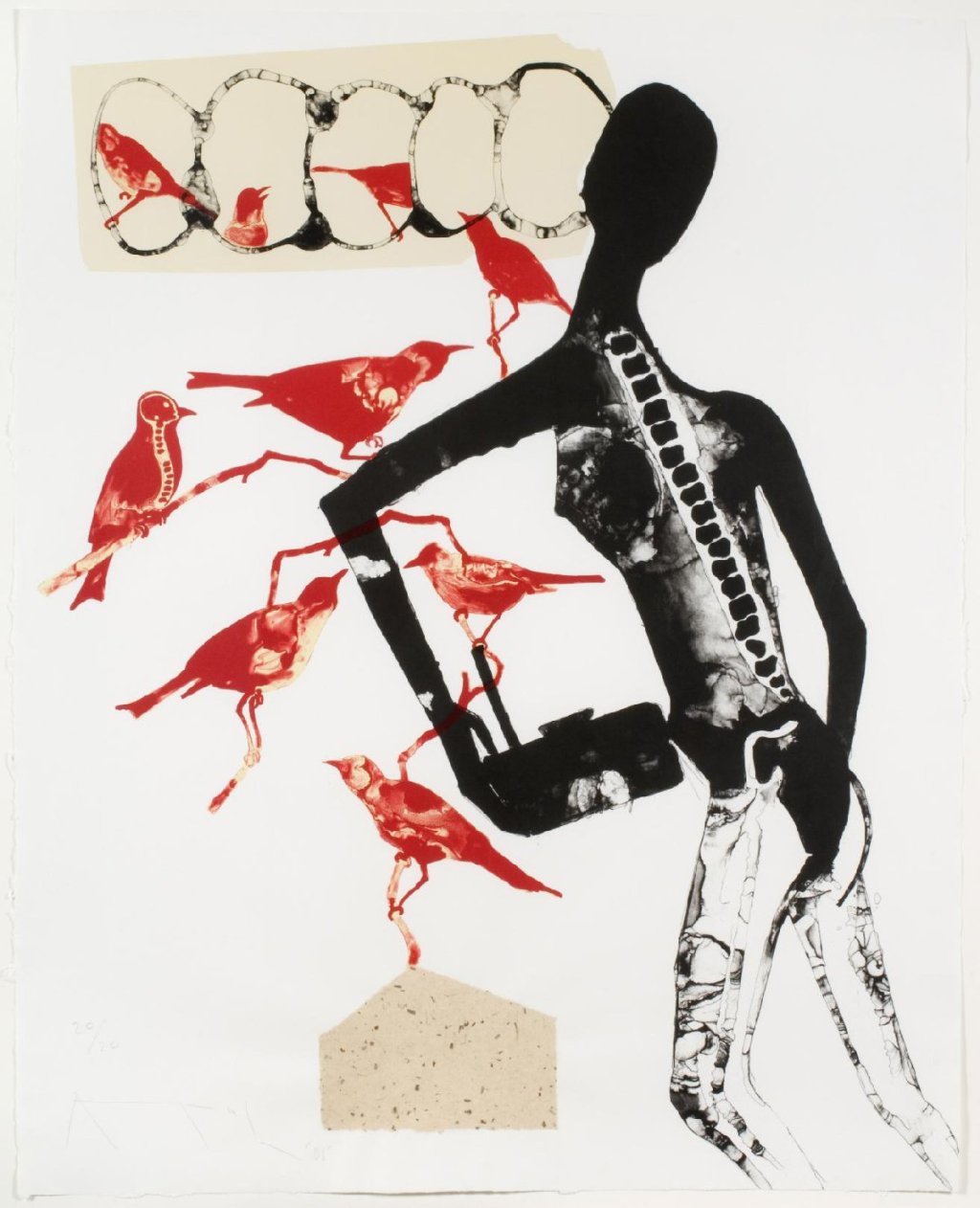

Sabari the hermit intertwines with the birds. Her arm seems to go through the branches, or maybe it’s posed in front, blocking a perfect view of their resting place. She poses like a model, her right arm in her pocket and her left at a right angle, her back arching while her neck cranes forward. I can’t help but wonder if her pose represents her contentment with the life of the birds or if she contorts her body to match the uncomfortable feeling. She both seems leaning away and towards the birds and the branches. She feels more at home with them, but dreams of a different life, one with people and fantasies. I’m struck by the notches of her spine, each one distinguished and layered and moving diagonally down her back. Maybe she’s aware of the way her spine ladders to the heavens, to the birds, that her body is combined with the fate of something more. It calls out to the way wings glide across the landscape, flap with each breath, continuing an effortless journey.

Sabari has never met the man that is destined to bless her, but yet she spends her life waiting for him, despite never venturing out of her tribe. Eternal happiness without effort. I used to write stories like that, used to read online stories where the two characters are connected by the red string of fate and continue to meet and fall in love in every universe imaginable. They called out to me when I was twelve, thirteen years old. The first thing I ever attempted to write was in a little worn out notebook that I took with me on a Girl’s Scouts trip. I was inspired by my friend, who was writing a story about werewolves in her own notebook and passing it along to all of us every time she finished a chapter, the length of which would be a couple pages. I remember the protagonist, a punk rock girl who hated stuff like the color pink and pop music, and her love interest, the half-man half-wolf that liked how she smelled and followed her around, were constantly breaking up and getting back together. My friend would show us the next few pages with a smile spreading on her face, waiting for us to discover whether or not the two would still like each other by the last sentence. I would tell her I enjoyed it, but it was the first time I thought I could do something better.

My notebook story, written while we’re getting ready to sleep in the upstairs room of the potato farm we’re visiting, didn’t have as much of an extensive plot. I gave up on it after one chapter. But it was supposed to be about a magical girl who loses all her memories—I wrote the scene where she wakes up in bed with a bloody bandage around her head and no recollection of the people around her—but is still destined to save her village from a dark force I never figured out, all alongside her childhood best friend. Him and her were meant to get together by the end. Their relationship was my pure motivation for writing, and the extent of any planning I did for that story. While our troop is out on the farm fields that day, watching tractors overturn potato crops from the loose dirt under a beaming sun and pointing out the black widows that have been upheaved from their dark homes, I daydream about my two characters’ pasts. Right before the start of the story, when my unnamed and unconceived villain thrashes their magical lightning at my protagonist, and her friend and companion runs to save her, cradling her in his arms. While she’s on the brink of death, he realizes that he loves her. He’ll be frustrated that she’s lost her memory and take it out on her, but really, he’s only frustrated at himself and his bad timing.

It was the age of an obsession of romance and love triangles in stories that were probably better without it. Hunger Games and whether you were Team Peeta or Team Gale was the gossip of the town. We bartered our two cents at the open market, spoilers and criticism and the ending of Mockingjay felt so rushed didn’t it, where did Gale even go, and Katniss wasn’t very convincing when she told Peeta she loves him, was she? What would Sabari and her birds think about the conflict, in her hut in a tiny tribe, waiting for the one man to free her? Would she root for the man Katniss is forced to share her trauma with, or would she root for the best friend who shares her goals, hobbies, and mindset? Or would she always prefer the company of the birds, the way the call of the Mockingjay draws Katniss and remembers her fight for the freedom of Panem.

Sabari is youthful sensuality, the notches of her spine on display for all to see, her arm angled on her hip so you know she’s feisty, with her army of birds ready to attack. She’s the perfect young adult literature protagonist, or the perfect protagonist for young adults to write about. She doesn’t need a man, of course not, which makes the fated relationship all the more exciting. We all know Sabari is a metaphor for waiting for a vision of God, but isn’t it so romantic when they finally meet?

My notebook story is circled around the troop, and then in the car on the way home the next day. The first girl—and I do her a service by not remembering her name—I showed it to asked me what I was writing.

“Is that a diary?”

I shake my head, with an embarrassed smile meant to say I totally didn’t want you to ask, but I’ll tell you all about it. “It’s a story I’m writing.”

She looks excited. “That’s so cool. What’s it about?”

“I’m not sure. Do you wanna read it?”

So she does. She oohs and aahs in all the right places as she flips through the notebook pages. She wants to see more. Then other girls gather around to read it. It seems to garner universal critical acclaim, except from the one girl who asserts Catherine is a dumb name and she should have something better, and that she feels like she’s read dozen of stories that sound like that.

She was right, but I’m the same amount of unprepared for criticism now as I was back then.

Sabari is the protagonist waiting for one man, but she has a higher quest; who would take care of her birds if she was not around? They are one and the same, exhibited by the loop of her arm through the branches. Her story forgets her livelihood and existence, the bird’s song she hears everyday, how she stands with them and protects them like it’s the only thing she’s ever known. Atul Dodiya asks if Sabari’s goal is to be blessed, or to be remembered.

I go back to school and write different stories in different notebooks. There’s one I try and commit to, a story about a girl and, once again, her male best friend who go back in time through historical events. I never got to the historical events. I wrote a scene where they argue with each other while on the bus. My friends read it and say, “Oh my god, that’s so cute! You have to give us more.”

I don’t think I did. I meant the arguing to throw people off the trail that I was going to make these two characters kiss, eventually, but it just seemed to foreshadow it. I forget about the story and only remember the planned relationship. It was left incomplete, the words permanently staining a notebook page that either sits in the closet of my childhood bedroom or got thrown out with all my seventh grade homework papers. The birds have been starving, morsels of food given and taken away and the source of the supply draining.

I’ve never committed to a novel, or even to a short story longer than a few thousand words. I have ideas, dreams of a fantasy/adventure saga as epic as Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter, but I fail to conceptualize an actual story. I’ve brainstormed and scribbled out plans for environmental allegories that seem so surface level a dog could probably pick up on the comparisons. But I always come back to a relationship. A story where Earth is divided between two planes of existence, the one we live and the hidden one based on indigenous American culture, the land slowly drying up and dying as we continue to pollute our current world. In my mental outline, the two girls, one from each plane, restabilize the connection through their love for each other (but don’t ask me how, I never got that far). In another, a team of superhumans collide with a research scientist who resents superheroes for being hailed as the world’s saviors. The big, epic, suspenseful climax culminates in her narrowly surviving the supervillain’s attacks while the leader of the superhero team is injured trying to save her. Only after I visualize the scene do I realize the similarities to my first story at twelve years old, and do I hear the words of my fellow Girl Scout: I’ve read dozens of stories like that before.

My word documents remain as unfilled as my notebooks. I fear crossing over into my self-indulgence, basing strong and independent protagonists’ goals on their feelings for someone else. Sabari stands out because she rejects her original story. This is who she is, not the old woman who only wishes to see God. She loves her birds and her spine and her ability to bend as she wants with no one to tell her she shouldn’t. If you didn’t know her story, you wouldn’t know a man, a god, had anything to do with how she stands and paints herself in her prime. The saddest fate of an author is to write a story your own protagonist would hate.

Leave a comment